Close-up on Luigi Colani, 1928-2019

He enlivened the 22nd edition of the Festival Automobile International, which was held in January 2007 for the second time at the Grand Palais; that year, Luigi Colani received the Grand Prix for Design. He passed away on 16 September at the age of 91.

It was thanks to policies in favour of aerodynamics that the designer Luigi Colani came to the forefront during the 1980s. In Germany, the Federal Ministry for Research and Technology (BMFT) commissioned a series of economical concept cars to be presented at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1981. The world was still reeling from the two oil crises which had brought to light the need to save energy.

As it happened, Colani had always made aerodynamic shapes his trademark.

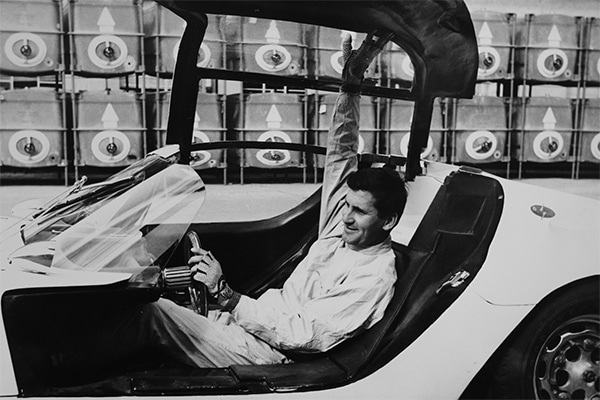

Lutz Colani – known as Luigi – was born in Berlin in August 1928; his father was a film-set designer, who passed on to him the name of a family from Ticino, while his mother was a Polish actress, who inspired in him a Slavonic sensitivity. After studying painting and sculpture at the Academy of Arts in Berlin, he worked for the coachbuilders Rometsch and Erdmann & Rossi. He spent ten or so years in France, before setting about the creation in Germany of sports cars based on a Volkswagen chassis. Even then, their lines were gentle and streamlined. The first Colani GT Spyder was assembled in 1962. The following year, a closed version of it was developed, with a glazed cockpit which swung open. Christened the “Whippet”, it was sold by Canadur GmbH & Co KG. In 1964, the Whippet was fitted with gull-wing doors. Next, Colani studied a prototype using a BMW 700 engine.

It was the start of a long and fruitful series of experimental models. In 1967, Colani filed a patent for the “C-Form”, which consisted of an upturned wing enclosed in pontoon-like structures, in essence the precursor of the “wing car” which became widespread in Formula 1 ten years later. This shape gave rise to numerous models and some rolling prototypes applying his principles: the GT90, Colambo, BMW M2 and New RS … Their styling was sensual, enveloping the cars’ aerodynamic elements and the different – and often ill-matched – parts of their bodies in a succession of lavish swirls.

In the 1970s, Colani laid the foundations for bio-design, whose organic shapes would influence design in the decades that followed. In 1981, Colani travelled to Japan to spread the word; he was welcomed there as a prophet and his designs reached every sector of industry. An exuberant character, a militant and undoubtedly a visionary, Colani used design as a political weapon. His words sang the praises of subversion, but his style was romantic. His life was a story of paranoia, but his work was that of a utopian.

Colani eschewed the established order. His influence, unspoken but widespread, was considerable. “Nature creates perfect forms”, he declared. “Straight lines do not exist in nature”: such was the credo of bio-design, which employed a vocabulary inspired by organic shapes. Everything in Colani’s world was made up of curves: his aeroplanes, motorcycles, pens, telephones, washbasins, cameras … and even his erotic underwear … Colani applied the theory of bio-design to all modes of transport, as with the “Megalodon” airliner in 1977, or to everyday objects such as a camera for Canon in 1983.

With his rounded, uterine shapes, Colani came across as a daydreamer, obsessed by a single idea, but throughout the world, designers were influenced by him and created smoother shapes.

Forever crying out, constantly in a state of revolt, Colani travelled to Japan to spread his gospel to the local designers. His ideas reached every sector of industry. Then he returned to Europe, “in order not to feel responsible for [its] collapse”. Colani denounced the cultural influence of America and declared himself ready to do anything to curb it: to work for the Russians, to teach design in Peking or to offer his services in the Lebanon or in Libya …

Several car makers consulted Colani, but they did not take up his proposals to put them into production unaltered. On the other hand, they were greatly inspired by them. From now on, bio-design would bring its organic forms to the car and be applied to interior design too, helping to create an environment which would protect and wrap around its occupants.

In 2007, dressed in white from head to toe, he received the Grand Prix for Design at the Festival in the Grand Palais from Jean-Michel Wilmotte and Rémi Depoix.

Hail the artist.